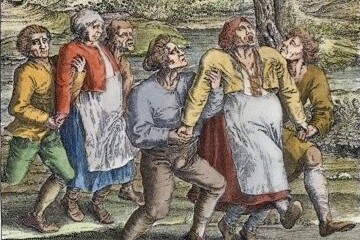

One July day in 1518, Frau Troffea left her Strasbourg house and started to dance. She didn’t want to; it just happened. She danced frantically in the street, finally collapsing from exhaustion. Then, after a rest, she got up and danced some more.

By the end of the week, at least thirty people had joined in. By August, there were almost four hundred dancers, victims of what became known as the Dancing Plague of 1518. They didn’t want to do it, either. Eyewitness accounts describe dancers screaming for help and begging for mercy.

Many claimed the dancers were either possessed or cursed. Doctors blamed the dance mania on “hot blood” and suggested the affliction could be danced away. This sounded like a plausible cure to civil and religious leaders, who hired professional dancers and musicians to help the victims continue dancing until the fever could leave their bodies. The results were predictable; pain from nonstop dancing transcends swollen feet. Some dancers died from exhaustion. Others succumbed to strokes and heart attacks.

Modern-day historians and doctors believe that the Dancing Plague of 1518 was an example of mass psychogenic disorder, a product of high anxiety and shared collective consciousness. There was plenty to be anxious about. Smallpox, plague, syphilis, crop failure … even leprosy had re-surfaced in Strasbourg. Residents also shared a common belief in dancing curses as punishment for sins, inflicted not only by St. Vitus but by angry spirits who inhabited the Rhine. To be stricken in this way made sense. It took only one person to actualize the fear by breaking into dance.

We’re fairly confident that something like the Dancing Plague could never happen to us. We aren’t as naïve as our sixteenth-century counterparts, and it’s hard to imagine that any situation could force us to act so bizarrely against our will.

Maybe, but …

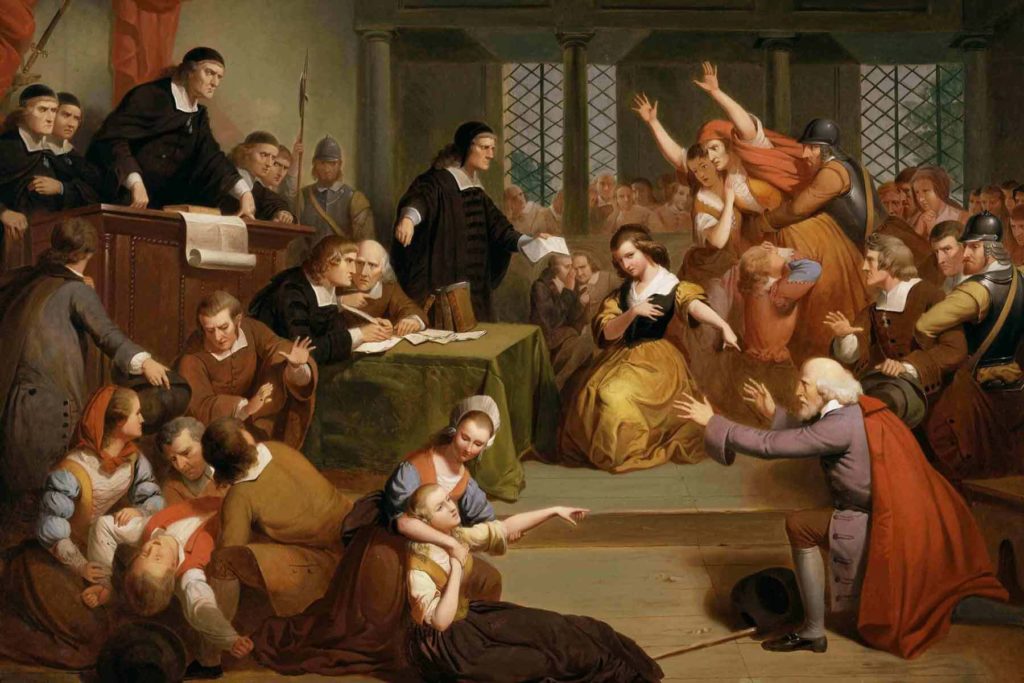

In 1692 Salem, Massachusetts, a trio of girls fell into fits and seizures that launched the Salem witch trials. In Meissen, Germany in 1905-1906, over two-hundred students were afflicted with unexplained twitching and trembling when given writing assignments. In 2006, approximately three-hundred Portuguese school-aged children complained of breathing difficulties and rashes, the power of suggestion traced back to an episode of a popular teen TV show. In October 2023, more than one hundred students at a girls’ school in Kenya were hospitalized with uncontrollable spasms and paralysis. There were no identifiable medical causes for any of these incidents, but plenty of anxiety to go around.

No matter what the era, humans have desires, hopes, and fears. Our stressors and anxieties may change, but we remain stressed and anxious. In fact, thanks to the internet, the 21st century serves up those things on tap, like a 24-hour open bar of calamity. Each of us juggles fear, both personal and generalized.

In Strasbourg, the dancing began to wane by September. Those still dancing were carted to a mountain-top shrine dedicated to St. Vitus, given red shoes sprinkled with holy water, and told to pray for absolution. Finally, the dancing stopped. After approximately six weeks and as many as one hundred deaths, the Dancing Plague of 1518 was over.

There’s safety in assuming ourselves above such extraordinary responses to fear and anxiety, but both emotions are insidious and can make us behave in ways we never thought we would. The more we consider ourselves immune to psychological distress, the more susceptible we are to letting it run amok in ways we regret.

Fascinating! It made me think of “Havana Syndrome” with people in the intelligence community in Cuba reporting strange symptoms that they thought (maybe this is still a theory) might be some kind of remote attack. Last I heard, it was still a mystery. And some defensiveness about the suggestion that it could be in any way psychological or power of suggestion.

I do think doomscrolling keeps us helplessly dancing through disaster…until at least in this case we realize we aren’t actually helpless and can put the phone or laptop away and, as the kids say, “go touch grass.”

Kristina, Havana Syndrome is starting to show up on lists of psychogenic disorders. I wonder how much time and research something requires before it gets chalked up to “Nope, no explanation here …”

“Touching grass” is hugely important, whatever your grass may be.

With my two lead feet, I suspect I at least would be immune. I could distribute bottles of water, maybe . . .

Bob, would that make you part of the problem or part of the cure?

Neither. Just mildly socially embarrassed, unless someone hands me a bass . . .